After many suicides, deaths and heart attacks of the PaK women settled in Kashmir post-2014, there was a first divorce last year. Saima Bhat met a Muzaffarabad lady living without any relation or shelter and desperate to go home after four years of her stay in Kokernag

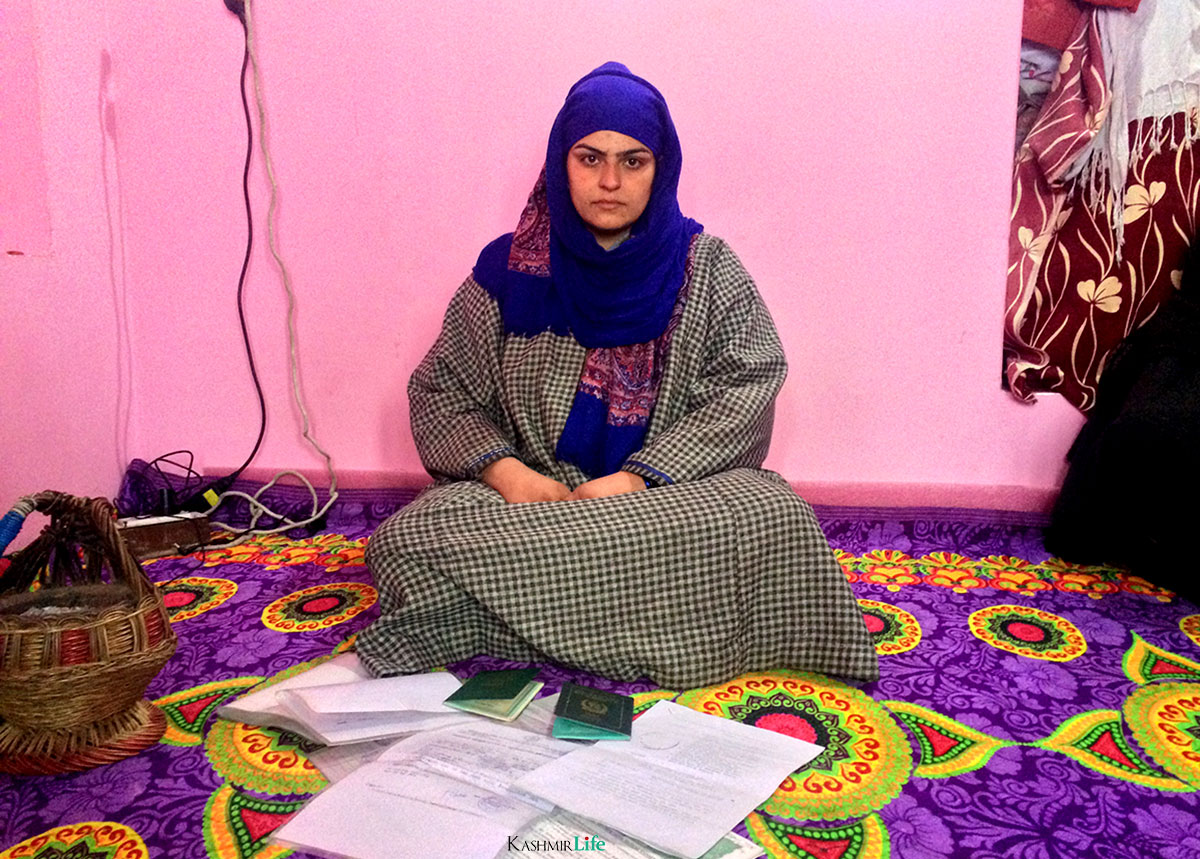

Kubra Geelani (KL Image)

By mid-January 2019, when a massive snowfall led to the closure of Jammu and Kashmir highway, one of the stranded passengers was a lonely lady, Kubra Geelani, 28, a just-divorced woman. With tears in her eyes and distress quite visible on her face, she stopped near three Kashmiri speaking men in Udhampur.

“When I saw her, she was alone, shattered and without money,” says Syed Ajaz, in his late forties, one amongst the three men. The trio hired a tempo till Ramban. Then they trekked up to Ramsoo amid the deadly landslides.

But the landslides and the falling stones became invisible for Syed Ajaz as Kubra started narrating her ordeal.

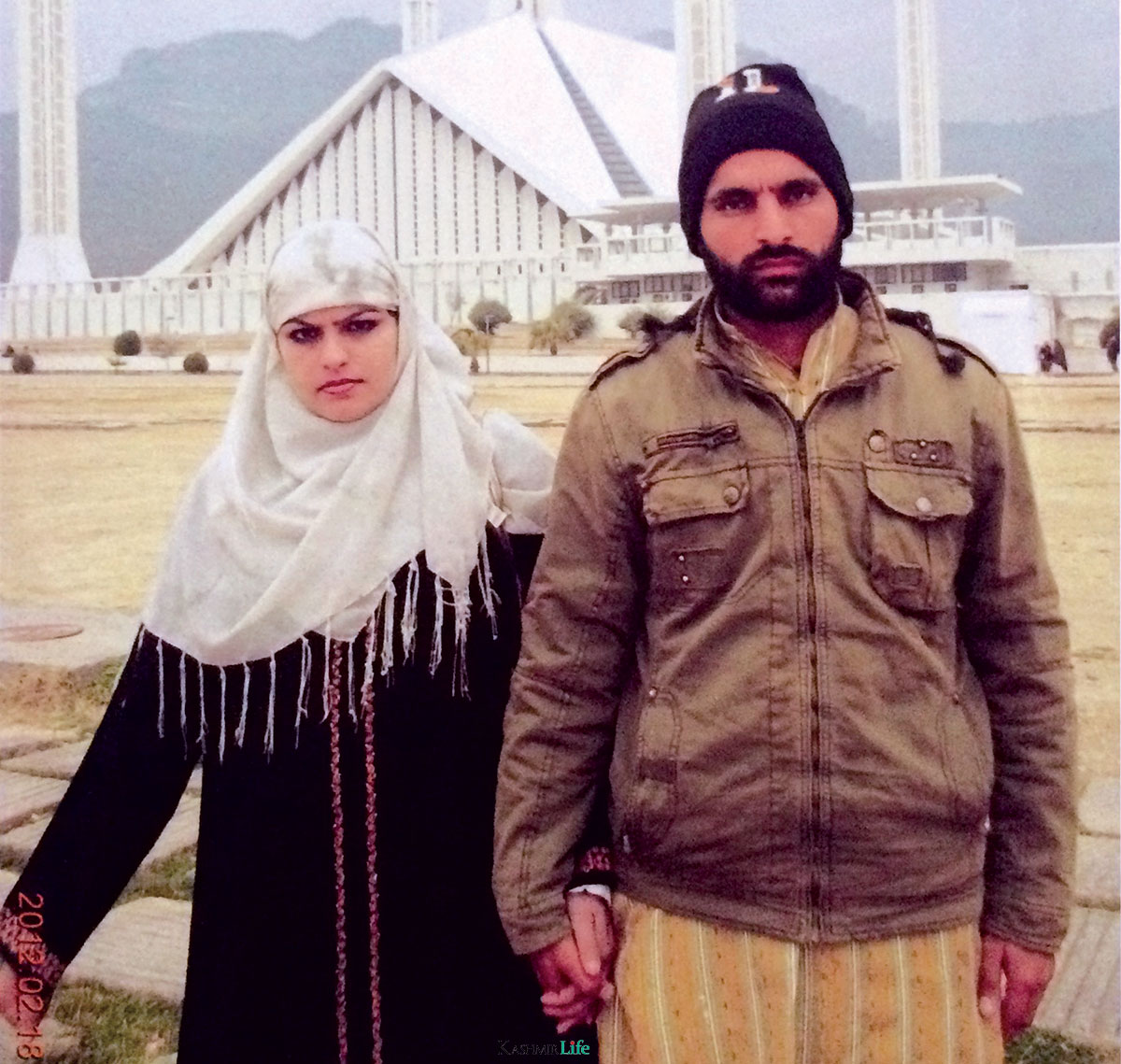

Actually, a Pakistan administered Kashmir’s (PaK) resident, Kubra had come to Kashmir with her husband, Muhammad Altaf Rather, an ex-militant, a resident of Panzgam (Kokernag), under 2010 rehabilitation scheme announced by the then chief minister Omar Abdullah. She was part of around 350 families who availed this policy.

The couple took marriage vows in 2010 and came to Kashmir in 2014 in search of ‘better’ and ‘secure’ living. But the relationship ended on November 30, 2018, with a divorce as Kubra couldn’t give birth to a child.

In an ‘alien’ space with no blood relation in Kashmir, Kubra is literally without a roof over her head. She has no source of income either. To survive she says she either begs or work as domestic help. She is longing for her home; though close-by, but far away actually.

A resident of Domail (Muzaffarabad), Kubra then 17, was married to Rather when she had passed her ninth class. It was an arranged marriage managed by her father Syed Lateef Hussain Geelani, a local Imam and an ex-serviceman.

Since childhood, Kubra said, she wanted to have better education and ultimately choose a career. But her dreams shattered after getting married. Post-marriage, she desired to “come to Kashmir, meet her in-laws, and speak fluent Kashmiri.”

Rather, her husband was associated with Hizb ul-Mujahideen, but after their marriage, he gave up his affiliations and started a livestock business.

A file pic of Kubra Geelani and her ex-husband Altaf Ahmad Rather in Islamabad, Pakistan.

After the successful return of many Kashmiri ex-militants along with their families, the desire of coming home grew for this couple as well. Finally, they also took the plunge for return. “We came via identified Nepal route, and after coming to Kashmir, we were kept at CIK Humhama Jail for three days,” Kubra said. “We were four families and after following proper bail procedures we were allowed to move towards our destinations.”

Towering and well-built, Kubra has sharp long eyebrows. She was excited to meet her in-laws in south Kashmir. But to her utter shock, Rather’s house turned out to be in Panzgam village of Kokernag, almost 22 km from the main district Anantnag (Islamabad). “That was my first shock, but still, I decided to manage everything as I was at my dream place,” Kubra said.

At Sogshali Panzgam, Kubra started living with her mother-in-law, brother-in-law, younger to her husband, and Rather’s uncle. Both the brothers were in the livestock business.

For the next four years, it became difficult for Kubra to manage her expenses as a result of which she started working as a domestic help in many well to do houses in the district. She said they used to pay her and even give her clothes.

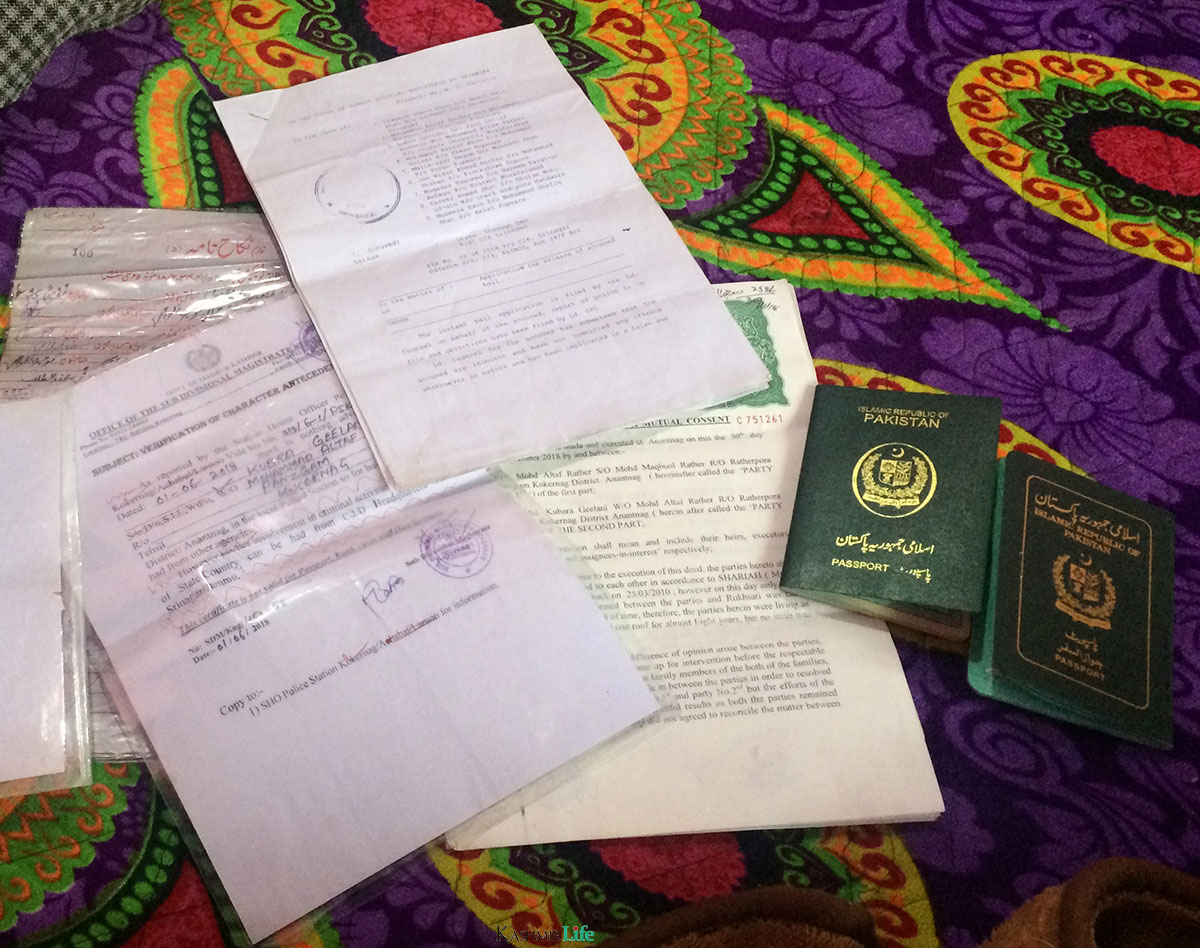

“I was managing it myself but then my husband decided to give me divorce as I couldn’t give him a child. He had the support of his family who wants him to marry another girl,” Kubra said. It is the same reason mentioned in her divorce deed, and ironically, the papers confirmed she was paid Mehr of Rs 1.5 lakhs at the time of her Nikah but after the divorce, she was not paid any alimony.

The couple separated in November. Before that, she had the information about her father being seriously unwell. “He had a desire to see me before dying and I ran from pillar to post along with my husband to go back to Muzaffarabad but nothing worked,” Kubra said. “After coming to know about my divorce, my father couldn’t survive. He died immediately after six days of getting the news of my divorce.”

Desperate to go back home, Kubra said, she met all the leaders– the Joint Resistance Leadership (JRL), former chief ministers, Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti. “They all promised me they will help, but so far, they have done nothing,” she said.

“See I don’t even have a roof over my head now.” Kubra is staying with a family of her married friend where she earlier worked as domestic help.

Initially, she had decided to rent a room and start a parlour either here in Anantnag or in Jammu. “But the person of my grandfather’s age was seeking a cost which I could not afford,” Kubra said and broke down. “Then, I took refuge in my friend’s home.”

Divorced and then orphaned, Kubra took all her documents and visited Delhi for a meeting with Pakistan Embassy. By the time she reached Delhi, it was already late and she decided to stay overnight in Delhi.

“I thought I’ll stay around Jamia Masjid where a Hindu helped me to get a better room, but on way to the place, I met a Kashmiri speaking boy,” Kubra said, almost crying. “Trust me I was happy to see a Kashmiri but when we talked he suggested we should book a room together. I swear I slapped him right there and started abusing him.”

Next day, she said, she met Fozia Madam in Pakistan Embassy who had already given her a renewed passport. “She knew my case well and she helped me in clearing all my documents for my return. I was happy that I was going back,” Kubra said. But, as they say, it was jumping out of the fire into a frying pan. At Wagah, Attari border, when she was weeping over the ‘bad’ days she spent in Kashmir, some official from the Indian Immigration stopped her and sought documents from her. “After checking all the documents I was stopped. They told me I can’t go as they don’t have orders from their seniors.”

Documents of Kubra Geelani

Shattered Kubra decided to come back to Kashmir, and on her way, she got stranded due to the closure of the highway.

After listening to Kubra’s ordeals, Syed Ajaz offered her the family’s hospitality. “I told her she is my daughter or a sister and I mean it,” Aijaz said. After reaching Kashmir, Kubra first visited her friend in south Kashmir and then reported to Syed Ajaz’s north Kashmir residence, where she is putting up since then. The family greeted her as if she is their blood relation.

Syeds live in Chukar, 7 kms away from Pattan. At Syed’s modest single storey house, Asif, the youngest brother of Aijaz, said they are helping Kubra in whatever means available to them. “We have sought help from our relative, former minister Basharat Bukhari and are planning to meet our former MLA as well,” he said. Asif has used his social networking sites where he is sharing Kubra’s video interview with a Pakistani news channel Bol TV endlessly. “I am sharing it with all high-level dignitaries because I want better sense should prevail and they should help Kubra to reach her home.”

Syeds want Kubra to live with them till any decision is taken about her return by the higher officials but she says she will be going back to her friend in south Kashmir. Ever since her divorce Kubra says her ex-husband has not contacted her to know if she is alive. “She keeps on weeping whole night and then her blood pressure shoots up,” said Aijaz’s wife.

Amongst the 350 families of ex-militants who returned under Omar Abdullah’s scheme, Saira, a resident of Karachi now living in Kupwara, says most of the ladies among them are undergoing treatments for depression.

“Two ladies committed suicide in Kreeri Pattan and Hajin Sopore, four got heart attacks including a male in Batamaloo, and one more lady passed away in Lal Bazar due to problems in her liver,” Saira said. “You will see all of the ladies undergoing treatment have mentioned on their prescriptions that they are in depression because of the longing for their parental homes.”

Kubra is longing for her parental home in the other part of Kashmir but she is not allowed to go. Her family in PaK including her mother, sister and two brothers are also desperate to get their daughter back. “My father was ill for nine months; when he wanted to see me, I could not go. After his death I am living with nightmares that what if my mother also dies waiting for me,” says Kubra.

While recalling her days in Panzgam, Kubra said their decision to return from PaK was a wrong step. “We were living a dignified living there. I guess my husband had the same opinion about this,” Kubra said.

A file photo of the families who returned back from Pakistan administered Kashmir protesting in Srinagar against government apathy.

“My divorce was my destiny but now the administration should not punish me for marrying a Kashmiri. I should be allowed to go home. I don’t have any blood relation here.”

After reuniting with her family, if at all she is able to, Kubra says, she will never ever think of Kashmir. “I am also a Kashmiri, but this Kashmir is too bad,” Kubra said bluntly. “Every bad thing has happened to me; I want to go home at any cost. Nobody has ever seen me as his daughter or a sister, be it politicians from Srinagar or Anantnag or locals whom I have visited from time to time for help. Everybody wanted to take advantage of me.”